Excerpted from The New York Review of Books

|

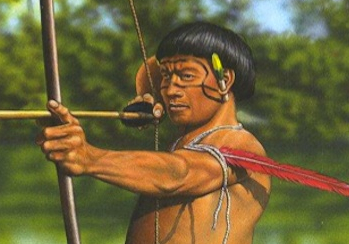

| A Yanomami man paints his face in preparation for an inter-village feast. |

The Falling Sky, by Yanomami shaman Davi Kopenawa and French anthropologist Bruce Albert, takes its title from a creation myth of the Yanomami people who live in the border region between Brazil and Venezuela. The primordial world was crushed by the collapse of the sky, hurling its inhabitants into the underworld. The exposed “back” of the previous sky became the forest where the Yanomami emerged, and where they remain to this day; they still call the forest “the old sky.” A new sky was erected, held in place by metal foundations set deep in the ground by the demiurge Omama. Yet the new sky is under constant assault by the forces of chaos, and Yanomami shamans work tirelessly with their spirit allies, the xapiri, to avert a new apocalypse. A diaphanous third sky already lies waiting, high above, in case the current one collapses and the world once again comes to an end.

...

The Falling Sky is several things. It is the autobiography of one of Brazil’s most prominent and eloquent indigenous leaders. It is the most vivid and authentic account of shamanistic philosophy I have ever read. It is also a passionate appeal for indigenous rights and a scathing condemnation of the damage wrought by missionaries, gold miners and white people’s greed. The footnotes alone harbor monographs on Yanomami botany and zoology, mythology, ritual and history.

Most of all, The Falling Sky is an elegy to oral tradition and the power of the spoken word. As denizens of the “Gutenberg galaxy”[1], we take for granted the superior fidelity and durability of the printed word over speech in transmitting knowledge through time. In his singular voice, Kopenawa, talking of xapiri spirits, turns this notion on its head:

I do not possess old books in which my ancestor’s words have been drawn. The xapiri’s words are set in my thought, in the deepest part of me… They are very old, yet the shamans constantly renew them… They can neither be watered down nor burned. They will not get old like those that stay stuck to image skins made from dead trees. When I am long gone, they will be as new and strong as they are now.

As both narrator and first author, Kopenawa addresses the reader directly: “You don’t know me and you have never seen me. You live on a distant land. This is why I want to let you know what the elders taught me.”

...

|

| A Yanomami shaman's apprentice in yãkoana trance. |

Yanomami shamans use a powerful hallucinogenic snuff, yãkoana, made from the resin of the nutmeg relative Virola elongata. By taking it, the shaman “dies” or “becomes other” and experiences the spirit world firsthand. Kopenawa renders these visions with images of haunting beauty:

The xapiri float down through the air from their mirrors to come protect us… Their mirrors arrive from the sky’s chest, slowly preceding them. They suddenly stop in the air and remain suspended… When they arrive, their songs name the distant lands they came from and traveled through. They evoke the places where they drank the waters of a sweet river, the disease-free forests where they ate unknown foods, the edges of the sky where, without night, one never sleeps.

...

[Of the gold mining that has wreaked destruction on his people and their territory], he remarks: “The things that white people work so hard to extract from the depths of the earth, minerals and oil, are not foods.” Drawing on myths and shamanic experiences, Kopenawa develops his own understanding of the destructive forces unleashed by mining. Digging deep underground threatens to “tear out the sky’s roots,” the metal foundations erected by the creator god the Omama demiurge to hold up the cosmos. He concludes that minerals are in fact “fragments of the sky, moon, sun, and stars, which fell down in the beginning of time.” These hot, dangerous “sorcery substances” were hidden by Omama in the cool depths of the earth. “Tearing these evil things out of the ground” and smelting them unleashes disease-ridden vapors. Epidemic illnesses are represented in the spirit world as cannibal beings living in “houses overflowing with merchandise and food, like gold prospectors camps.”

These illnesses make not only the Yanomami sick, but the sky itself:

The sky… is getting as sick as we do! If all this continues, its image will become riddled with holes from the heat of the mineral fumes. Then it will slowly melt, like a plastic bag thrown in the fire… If the sky catches fire, it will fall again. Then we will all be burned, and we will be hurled into the underworld like the first people in the beginning of time.

...

Of the “Merchandise Love” that he sees at the root of white people’s greed and destructiveness, he states with prophetic moral clarity: “Merchandise does not die… When a human being dies, his ghost does not carry any of his goods onto the sky’s back, even if he is greedy.” Kopenawa also perceives how the shamanic path has set him apart from ordinary Yanomami: “If you do not become other with the yãkoana you can only live in ignorance. You limit yourself to eating, laughing, copulating, speaking in vain, and sleeping without dreaming much.”

The anthropologist Napoleon Chagnon is mentioned briefly at the end of the book. However, especially in Chapter 21, where Kopenawa contrasts Yanomami traditional revenge killings with the Western phenomenon of total war, Chagnon’s controversial legacy looms large, as does Albert’s own editorial hand. This chapter seems to recapitulate, in Kopenawa’s voice, the same arguments Albert has leveled against Chagnon in heated scholarly debates.[2] As a cultural anthropologist, Albert sees Yanomami warfare from the native point of view: an integral part of mourning practices that aim at erasing all traces of the dead person (including cremated bones) and quickly sating grief-fueled rage through revenge on the individual killer or sorcerer. Chagnon’s widely cited sociobiological theory reduces Yanomami warfare to a Darwinian contest among males to capture women and procreate.[3] Albert and others[4] have used Chagnon’s own data to refute the central claim that “fiercer,” more homicidal Yanomami men have more offspring.

...

There is little doubt from Kopenawa’s own words that the Yanomami value bravery, revenge and the warrior ethos, though many other things besides. In his frank language, Kopenawa refers often to his kinsmen’s preoccupation with “eating vulvas”; the fact that the verb “to eat” is a euphemism for both intercourse and killing suggests that the Yanomami, like many people, see sex and violence as somehow related, if not in the causal sense suggested by Chagnon's hypotheses.

Kopenawa concludes by reflecting on the profound cultural changes that have turned this warrior ethos outward towards new threats: “The words of warfare have not disappeared from our mind, but today we no longer want to harm ourselves this way.”

|

| The new Yanomami warrior-shaman armed with a hovering laptop (Image: Sergio Macedo). |

---

Read the full review in the Nov. 6 issue of

The New York Review of Books

The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman

by Davi Kopenawa and Bruce Albert

Translated from the French by Nicholas Elliott and Alison Dundy

Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 622 pp., $39.95

Read more from this blog: An Ax to Grind: Napoleon Chagnon, the Yanomami and the Anthropology Tribe

References: The New York Review of Books

The Falling Sky: Words of a Yanomami Shaman

by Davi Kopenawa and Bruce Albert

Translated from the French by Nicholas Elliott and Alison Dundy

Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 622 pp., $39.95

Read more from this blog: An Ax to Grind: Napoleon Chagnon, the Yanomami and the Anthropology Tribe

[1] M. McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (University of Toronto Press, 1962).

[2] B. Albert, “Yanomami ‘Violence’: Inclusive Fitness or Ethnographer’s Representation?” Current Anthropology, Vol. 20, No. 5 (1989).

[3] N. Chagnon, “Life Histories, Blood Revenge, and Warfare in a Tribal Population,” Science Vol. 239, No. 4843 (1988).

[4] B. Ferguson, “Materialist, Culturalist, and Biological Theories on Why the Yanomami Make War,” Anthropological Theory Vol. 1, No. 1 (March 2001).